The debate of Functional Programming vs Object‑Oriented Programming has shaped software development thinking for decades. Should you model your system using classes, mutable state, and encapsulated data? Or is designing pure functions, immutable values, and composition a more scalable and maintainable approach?

In this comprehensive guide, we compare both paradigms across key dimensions—conceptual philosophy, code organization, state and side effects, scalability, tooling, performance trade‑offs, ecosystem support, learning curve, and real‑world use cases—so you can make an informed decision about which suits your next project.

Philosophical Foundations

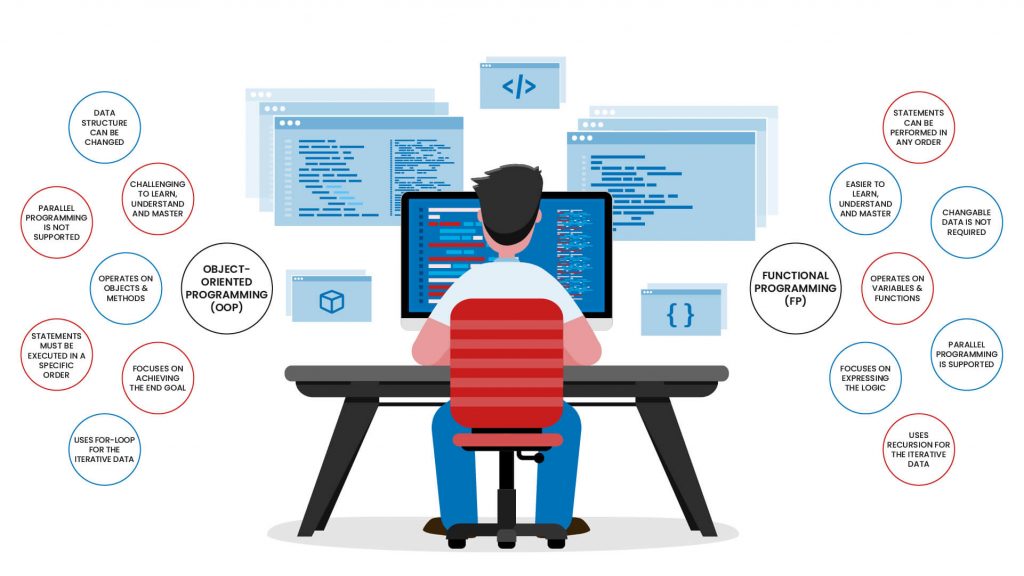

At its core, the contrast of Functional Programming vs Object‑Oriented Programming revolves around how developers approach modeling data and behavior. Object‑oriented programming (OOP) treats data and behavior as bundled in objects or classes. Objects encapsulate state and expose methods that manipulate that state.

In contrast, functional programming (FP) centers around pure functions—stateless transformations from inputs to outputs—with immutable data and higher‑order composition. Where OOP emphasizes responsibilities and encapsulation, FP emphasizes composition, predictability, and referential transparency.

Code Organization and Modularity

In an OOP system, you decompose your application into classes (or prototypes) intended to represent entities or components in your domain. Each class holds mutable state, lifecycle logic, and exposes methods that modify internal properties. Polymorphism and inheritance help share behavior across types. Conversely, FP encourages building small, composable functions that do not share mutable state.

You compose functionality by chaining or piping function calls, leveraging first‑class functions, currying, and function combinators. Thus the organization in OOP is based on entities and their methods; in FP it’s based on pipelines of transformations.

State Management and Side Effects

A core dimension in Functional Programming vs Object‑Oriented Programming is how each paradigm handles state changes and side effects. OOP typically encapsulates state within objects and encourages methods that mutate that state. Side effects flow through public APIs and internal encapsulation boundaries. Managing global state or shared mutable objects can introduce complexity as codebases grow.

FP, on the other hand, treats data as immutable and discourages mutations. Instead of writing code that alters state, you transform values and return new results. Side effects—such as I/O, network calls, or logging—are isolated to specific pure/impure boundaries. This isolation makes reasoning about code easier, enables easier testing, and reduces bugs from shared mutable state.

Error Handling and Control Flow

In Functional Programming vs Object‑Oriented Programming, error handling and control flow conventions diverge significantly. OOP languages often rely on exceptions and try‑catch constructs. The developer uses inheritance or interfaces to create typed error hierarchies. FP typically employs constructs like Option, Maybe, Either, or Result types, modeling potential absence or failure via types rather than exceptions.

Control flow in FP often takes the form of chaining monadic or applicative structures, enabling declarative composition without jumping into try‑catch blocks. These constructs encourage the developer to explicitly handle error cases at each step, leading to safer code for workflows like parsing or async operations.

Concurrency and Parallelism

One of the biggest practical debates in Functional Programming vs Object‑Oriented Programming concerns how concurrency is handled. OOP languages frequently rely on mutable state protected by locks or messaging systems (e.g. actors) to coordinate concurrency. Locking complexity and race conditions become real challenges at scale.

FP, built around immutability and stateless functions, avoids many common concurrency pitfalls. Pure functions can run in parallel without threat of shared state mutation. FP languages often support features like immutable data structures, software transactional memory (STM), or actor models that integrate seamlessly with pure function pipelines.

This makes functional approaches naturally amenable to concurrent and parallel workloads.

Performance and Efficiency

While Functional Programming vs Object‑Oriented Programming includes performance trade‑offs, the differences depend highly on language and use cases. OOP can be more efficient in certain contexts—like leveraging object reuse, mutable buffers, or in‑place updates—especially when implemented in highly optimized VM environments like Java or C#.

On the other hand, FP’s reliance on immutability can introduce overhead in memory allocation and copying. However, many functional languages and runtimes (e.g. Haskell, Scala, Elixir, Clojure, F#) use persistent data structures, tail‑call optimization, and efficient lazy evaluation to mitigate differences.

Complexity also arises from the specific problem domain: streaming data pipelines, reactive systems, or parallel workloads often benefit from FP’s concurrency safety. Meanwhile, standard monolithic business‑domain logic or GUI applications might fit more naturally in an OOP approach.

Tooling, Ecosystem, and Language Support

When weighing Functional Programming vs Object‑Oriented Programming, one must consider ecosystem maturity and tooling. OOP languages like Java, C++, C#, Python, or Ruby benefit from decades of libraries, frameworks, IDEs, debuggers, and documentation. Teams are comfortable with making classes, dependency injection, object hierarchies, and typical design patterns.

Functional languages are growing in popularity, but ecosystems may be less mature, depending on the language. Haskell or Elm adopt FP wholeheartedly, but community size is smaller. Languages like Scala, Kotlin, F#, JavaScript (via Elm, Ramda, RxJS), Clojure, or Elixir offer functional paradigms within a larger ecosystem.

These languages balance functional and object‑oriented features, letting developers choose paradigms contextually. Tooling for FP may include property‑based testing, advanced type systems, functional reactive programming libraries, and data‑flow visualization tools for stream or reactive systems.

Learning Curve and Team Productivity

One major distinction in Functional Programming vs Object‑Oriented Programming lies in how quickly teams adapt and become effective. Most developers learn OOP first in universities or bootcamps; class hierarchies, objects, encapsulation, and inheritance are familiar. Adopting FP requires understanding pure functions, recursion, higher‑order functions, lazy evaluation, functors, monads, and immutability.

This can feel abstract and lead to slower ramp‑up. However, once the team internalizes these concepts, FP often yields fewer bugs, easier refactoring, and clearer reasoning about side effects. Hybrid languages like Scala or Kotlin allow gradual migration, so teams can slowly adopt FP techniques while still using traditional OOP features.

Maintainability and Complexity Management

Comparing Functional Programming vs Object‑Oriented Programming in terms of maintainability, each has advantages depending on scale. OOP, with design patterns like SOLID, dependency injection, and layered architectures, can scale well—if designed carefully. But without discipline, large OOP systems can devolve into tangled class hierarchies and hidden mutable state, making unintended side effects harder to debug.

FP’s emphasis on pure functions and stateless transformations leads to code that’s easier to test, refactor, and reason about. Since any function’s output depends only on inputs, changes are more localized and side effects controlled. This leads to codebases where modification habits scale linearly with feature growth.

Real‑World Use Cases and Industry Adoption

In many organizations, pragmatic choices impact the Functional Programming vs Object‑Oriented Programming decision. OOP remains dominant in enterprise environments, especially those using Java, .NET, or applications with strong GUI, user‑interface, or domain‑modeling needs (e.g. ERP, CRM, desktop apps).

Functional programming is increasingly popular in domains that benefit from high concurrency, correctness guarantees, or data pipelines—think telecommunications (Elixir/Erlang), finance (Haskell, Scala), reactive UI frontends (React with functional patterns), distributed messaging systems, or compilers.

Some teams adopt a hybrid strategy: they model the core data processing in a functional style, while building UI and integration layers in a more object‑oriented manner, blending the best of both worlds.

Migration Strategies and Hybrid Approaches

Rather than choosing Functional Programming vs Object‑Oriented Programming in absolute terms, many organizations adopt a hybrid or migration strategy. For instance, an existing Java codebase can gradually introduce functional libraries like Vavr, functional data structures, and pure transformations. Similarly, JavaScript codebases can incorporate Ramda or Lodash‑fp and shift towards immutable data and declarative function pipelines.

In new projects, teams can prototype core logic in a functional language like Elm or Haskell for correctness, and handle integration or UI layers in familiar object‑oriented languages. This gradual strategy reduces risk while teaching functional concepts to a team without a steep learning curve.

Summary Comparison Table

| Dimension | Object‑Oriented Programming | Functional Programming |

|---|

| Philosophy | Encapsulates state and behavior in objects | Pure functions, immutability, composition |

| Code Organization | Class‑based, entities, methods, inheritance | Composable functions, pipelines, reusability |

| State Management | Mutable state encapsulated in objects | Immutable data, side effects isolated |

| Error Handling | Exceptions, try‑catch | Option/Result types, explicit handling |

| Concurrency | Shared mutable state, locks, threading | Pure parallelism via functions, actors, STM |

| Performance Trade‑offs | Efficient local changes, object reuse | Persistent data structures, functional optimizations |

| Tooling & Ecosystem | Mature, broad, enterprise standards | Growing, specialized, hybrid language options |

| Learning Curve | Familiar to most developers | Steeper initial learning, clearer reasoning |

| Maintainability | Good with discipline and design patterns | High, due to testability and stateless functions |

| Ideal Use Cases | UI‑driven apps, domain modeling, enterprise | Data pipelines, reactive systems, high concurrency |

| Hybrid Strategy | Apply functional techniques gradually | Blend FP logic with OOP frontends or tooling |

Conclusion

The debate of Functional Programming vs Object‑Oriented Programming is not about declaring a winner, but about choosing the right tool for the right job. Object‑oriented programming remains powerful for modeling domain objects, building rich user interfaces, and integrating with enterprise patterns. Functional programming shines in creating predictable, testable, concurrent, and maintainable systems with fewer runtime surprises.

Often, the best approach is a hybrid one—leveraging FP where purity and composability matter, and OOP where object modeling and ecosystem maturity offer advantages.

If you’re starting a new greenfield project focused on data pipelines, distributed systems, or reactive architecture, leaning functional can accelerate development and decrease bugs. In contrast, for standard web apps, business systems, or UI-heavy products, an object‑oriented core may offer speed and familiarity.

Whichever paradigm you choose, being cognizant of both perspectives—and knowing how they compare—is essential for designing robust, scalable, and maintainable software in today’s landscape.